Judah Grunstein thinks that the "barriers to exit" in Libya are actually pretty low; since the Obama administration didn't spend months demonizing Gaddafi, they have more wiggle room in dealing with him:

Nevertheless, the absence of such a campaign of demonization now allows for a wider range of political approaches toward Gadhafi's regime than were imaginable in Iraq, to take just one example, where not only did Saddam Hussein need to go, but the military needed to be disbanded and the Baathist party purged from the political arena. Similar to its approach in Egypt, the U.S. can actively pursue a policy of impeachment, as opposed to regime change, in Libya, which opens the door to a political settlement of both the civil war as well as the U.S. and Western intervention in it -- even as that intervention continues. In other words, this signals America's return after a decade's hiatus to a Clausewitzian approach to war more applicable to the kinds of limited conflicts we're likely to face moving forward.

I'm not so sure it's going to play out so neatly. First, as Grunstein points out, the Obama administration has stated that its policy in Libya is that Gaddafi must no longer rule Libya. That is, Obama's policy is regime change, even if, for the moment, he is not matching military means to his stated ends.

It's true that removing Gaddafi from power is a more limited goal than transforming Libya into a model democracy in North Africa, but I don't see how the president has given himself much room to maneuver toward a political settlement. Obama's opening position is that Gaddafi loses power. Gaddafi's opening position is that Gaddafi stays in power. Unless one side backs down, it's a zero-sum standoff.

(UPDATE: To clarify, Grunstein is contrasting Libya to Iraq, where the goals were a root-and-branch removal of Hussein and senior officials in the Baath party, where in Libya, President Obama just wants a single person ousted but could conceivably deal with other members in Gaddafi's inner circle.)

Meanwhile, Shadi Hamid thinks I define U.S. interest too narrowly:

Some people might take issue with "moral imperatives" or how morality is very much part of how I conceptualize broader U.S. interests. But we aren't France (and even France has taken to talking about the honor of the West in face of dictatorship). We are the United States and the U.S., for both better and worse, has claimed to be a nation that stands for something beyond the nation-state. That's why people look to us for moral leadership, even if they're likely not to find it. We are not Botswana. And the president of the United States is not the premier of China. Moreover, it is declared U.S. policy under both the Bush adn Obama administrations that the U.S. will support the universal, democratic aspirations of the Arab people. In this sense, we have encouraged them to do what we would do in similar circumstances - resist repression and fight for their freedom.

I have, respectfully, two problems with this. The first is that invoking morality is a complex and often dubious standard. Once we declare that we have a moral obligation to act in Country X then we have an open-ended commitment to intervene everywhere our moral sensitivities are inflamed.

If, on the other hand, we declare we have a moral obligation to act if the country can't really fight back, doesn't have a great power patron, isn't hosting American military bases, is regionally important, or is rich in natural resources, then it's not actually morality that's guiding our hand, is it? Morality is just one ingredient, and self-evidently not the decisive one, or else we'd be marching off into Burma, Yemen, Somalia, et al.

Giving undue emphasis to morality in cases such as our involvement in Libya's civil war is therefore fundamentally dishonest - both to the American people about the reasons their blood and treasure are being put on the line, and to a global audience as well, since it could raise expectations of American aid in future conflicts. Mind you, I am absolutely not implying that people aren't sincere in their moral outrage or in their view that morality should play a major role in guiding U.S. decision-making. But at the political level, it's just not the case that morality alone is the guiding factor, and saying otherwise - or playing up the moral aspect of specific policies - isn't very clarifying.

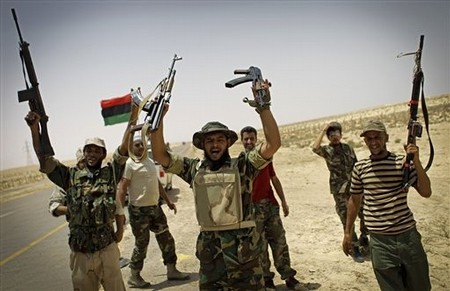

The second, and more practical problem with the morality standard is that there is no way whatsoever to ensure that American intervention will actually bring about a free and democratic Libya. Hamid argues that we're intervening on behalf of freedom fighters, but what do we know about them and their aims? Ronald Reagan once hailed the Afghan Mujahadeen as freedom fighters, but they were, by any reasonable standard, not interested in freedom and certainly not interested in the other values America stands for.

So what can we possibly know about how Libya's freedom fighters would rule the country if given the chance? All I know of the Libyan opposition is what I've read in the papers, so I will readily stand corrected if evidence can be presented showing that the proclivities of Libyan society (not just the elite portion currently asking for Western assistance) is toward pluralism, freedom, respect for minorities and women's rights, and all the other values Americans stand for. Or, if they don't, that they U.S. has divined some mechanism that can enforce and institutionalize those norms in the wake of Gaddafi's ouster. Barring that, we don't actually have an argument on behalf of fighting for freedom, but on behalf of people who want to take power from an admittedly loathsome dictator.