Talking Points

UK Labor Leader Ed Miliband shows you how to stick to your talking points. It's downright surreal.

[Hat tip: Ben]

« May 2011 | Blog Home Page | July 2011 »

UK Labor Leader Ed Miliband shows you how to stick to your talking points. It's downright surreal.

[Hat tip: Ben]

Peter Beinart dings President Obama for failing to level with the American people about the consequences of a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan:

Even if we stayed for 20 years, building a government that can stand on its own might be beyond our capacity. We’d go broke trying, and there is little reason to believe the future of this Afghan government is vital to U.S. security. Barack Obama didn’t even say so in his speech.But Obama did imply that his administration’s surge has so weakened the Taliban that they’ll trade their weapons for negotiations and eventually join the current government, thus allowing the U.S. to leave an Afghanistan headed towards peace. That’s what Mr. Amini was disputing. There’s an honest way to advocate for withdrawal from Afghanistan and a dishonest way. The dishonest way is to suggest that we’ll leave behind a government that can secure the country and a political process than can end the war. The honest way is to acknowledge that the Afghanistan we leave behind will be a chaotic, ugly place where the Taliban rules large swaths of the country, and much of what we have built may be washed away.

That's a winning message to take into 2012, isn't it?

But seriously, spinning the U.S. withdrawal doesn't make a lot of sense. I suspect most Americans understand that the U.S. will leave Afghanistan much as we found it - at war with itself.

(AP Photo)

Aaron Blake writes today on Tim Pawlenty's hawkish stance on foreign policy, a position he identifies as being an attempt to distance the former Minnesota governor from the rest of the field - or more accurately, from Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman:

Pawlenty appears to be trying to set the issue backdrop and shape the policy debate in the Republican presidential field, laying out high-minded goals and daring his opponents to jump on board.To some extent, Pawlenty’s aggressive approach has worked. The Pawlenty campaign’s comments critical of Romney and Huntsman on foreign policy have fed a debate about the GOP’s supposed isolationism.

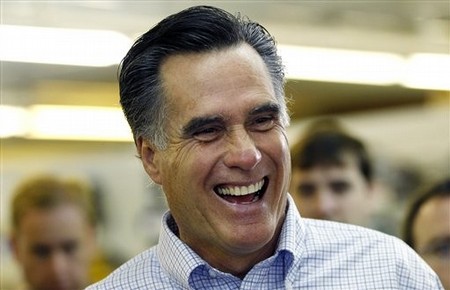

Romney’s campaign made clear immediately after the debate two weeks ago that he hadn’t shifted his foreign policy in any significant way and remained committed to strong national defense.

Huntsman’s campaign, too, is working to highlight that his position on Afghanistan does not imply any kind of unwillingness to act internationally — rather that he prefers a different approach.

“Jon Huntsman is the only candidate who has the foreign policy experience to know the threat and to understand the best way for America to protect our core national security interests,” Huntsman spokesman Tim Miller said in response to Pawlenty.

On today's edition of Coffee and Markets, I discussed this issue further with Pejman Yousefzadeh, who has been more supportive of Huntsman's campaign but no less skeptical about his position on Afghanistan. Within this conversation, I note my concern about Huntsman's position, and Romney's as well to some degree: that in attacking Obama from the left on America's role in the world, they will take an outlier view within the right's coalition and transform it into something more acceptable.

If you rewind back to the mid-1970s, when the president in power was one who draws the most comparisons to President Obama today - squandering an opportunity for economic growth, offering an uncertain view when it came to foreign affairs - a challenger emerged in Ronald Reagan, who tried to unify what he thought could be a new governing coalition for the Republican party.

This would not be the Nixon coalition, but something very different. And if you could pinpoint the moment this became a reality - that true modern Republicanism came into being - a strong case can be made for the 1976 Convention, when Gerald Ford invited the California governor to come forward and say a few words to the convention audience that loved Reagan but had (always the 'his turn' choice, those predictable Republicans) chosen Ford.

The off the cuff speech was a turning point for the party in more ways than one, as Reagan stood next to Ford and Nelson Rockefeller. Ford's campaign had turned to Reagan as an afterthought - according to Reagan staffer Craig Shirley, the Ford camp had sprung the opportunity at the last minute, hoping that an unscripted Reagan would turn out to be an incoherent one. Instead, Reagan outlined his views in a way that quickly convinced many in the audience that they had nominated the wrong man. And in doing so, he rejected the play-it-safe diplomatic approach their administration had adopted in their attitude toward the Soviet Union, endorsing a confrontational policy, and reiterating his call for victory as the only acceptable aim of government:

I had an assignment the other day. Someone asked me to write a letter for a time capsule that is going to be opened in Los Angeles a hundred years from now, on our Tricentennial. It sounded like an easy assignment; they suggested I write something about the problems and issues of the day, and I set out to do so, riding down the coast in an automobile, looking at the blue Pacific out on one side and the Santa Ynez Mountains on the other, and I couldn't help but wonder if it was going to be that beautiful a hundred years from now, as it was on that summer day. And then, as I tried to write, let your own minds turn to that task. You're going to write for people a hundred years from now, who know all about us; we know nothing about them, we don't know what kind of a world they'll be living in. And suddenly I thought to myself, if I write of the problems, they'll be the domestic problems, which the president spoke here tonight, the challenges confronting us, the erosion of freedom that has taken place under Democrat rule in this country. The invasion of private rights. The controls and restrictions on the vitality of the great free economy that we enjoy. These are our challenges that we must meet.And then again there is that challenge, of which he spoke, that we live in a world in which the great powers have poised and aimed at each other horrible missiles of destruction, nuclear weapons that can in a matter of minutes arrive in each other's country and destroy virtually the civilized world we live in.

"And suddenly it dawned on me: Those who would read this letter a hundred years from now will know whether those missiles were fired. They will know whether we met our challenge. Whether they have the freedom that we have known up until now, will depend on what we do here. Will they look back in appreciation and say thank God, for those people in 1976 who headed off that loss of freedom, who kept us now a hundred years later free, who kept our world from nuclear destruction, and if we fail, they probably won't get to read the letter at all because it spoke of individual freedom and they won't be allowed to talk of that or read of it.

"This is our challenge. And this is why here in this hall tonight, better than we've ever done before, we've gotta quit talking to each other and about each other and go out and communicate to the world, that we may be fewer in numbers than we've ever been, but we carry the message they're waiting for. We must go forth from here united, determined, and what a great general said a few years ago is true: There is no substitute for victory.

Reagan's adoption of this robust foreign policy view, viewing détente as an unacceptable goal, was expanded upon in his subsequent addresses, particularly his 1977 address to CPAC explicitly outlining the idea of the three legged stool - a combination of fiscal conservatives, social conservatives and those who believed in a robust defense of freedom and liberty to form a governing coalition. It has been the defining element of Republican policy in that time. And ever since Reagan, Republicans have chosen to nominate individuals who adopt all three legs of the stool. Time and again, whether John Anderson, Pat Buchanan or Paul himself, Republicans have rejected potential nominees who ditched defense/foreign policy leg, just as they have rejected candidates like Rudy Giuliani who rejected the social policy element. You haven’t had anyone who has rejected any one part wholesale.

So Republican leaders are, and should be, concerned about the moment they face. In my interview with Buck McKeon last week he noted that "Right now the stool is a little out of balance because fiscal matters are dominating everything, because of the economic shape we're in." But what if this is not a temporary circumstance, but one that could become permanent?

Tea Party favorites like Jim DeMint, Marco Rubio and Michele Bachmann have espoused traditional Republican views toward Afghanistan, expressing concern that the president's drawdown is too rapid. Yet others like Mike Lee and Rand Paul have crossed partisan lines to urge even speedier withdrawals. All these people are Republicans, of course. And so is Ron Paul, though no fair observer would argue his foreign policy views are representative of the Republican Party, or even a large percentage of the conservative base. Yet because DeMint, Rubio, Bachmann, and other Tea Party leaders spend a great deal more time talking about fiscal issues these days, for obvious reasons, they leave a vacuum filled by speakers who do not share their conservative views.

It's unlikely that Huntsman's race for the nomination ends up as any more successful than Giuliani's (especially considering his apparent decision to repeat Giuliani's tactical mistakes in Florida). But in adopting a position which criticizes Obama from the left as a key element of his campaign, Huntsman fills that vacuum, lending credence to the idea that such views represent the future foreign policy position of the Republican Party.

As long as the foreign policy leg of the stool remains undefended or ignored by many of those who the Republican base respects, a larger portion of the conservative base may be willing to consider wrecking the triumvirate entirely. Pawlenty's remarks were mostly good, but they take place in the context of a temporary primary battle - and Pawlenty is no Tea Partier. It will take considered effort, by those who are unsullied by past endorsements of domestic big government and can speak directly and convincingly to the conservative base, to reiterate why a robust defense of freedom and liberty around the world was right thirty years ago, and is still right today.

(AP Photo)

Daniel Larison continues the discussion about ideology and the rise of China:

I agree that ideology is an instrument of state power, and ideology as such wouldn’t exist except for the desire to acquire and exercise power, but this is what still leaves me puzzled. It doesn’t help the U.S. gain much of anything to stoke hostility towards China, and it isn’t clear to me that it is all that useful to the U.S. to try to encourage regime change in China. America won’t benefit from conflict with China, and it won’t benefit from prolonged instability in China and East Asia. If deploying liberal democratic ideology were actually being used to advance some concrete U.S. interest, that would be one thing, but instead it seems to have become an end in itself that requires the U.S. to put its interests at risk for the sake of prior ideological commitment.

I don't think the Obama administration (or the Bush administration for that matter) has ever been so bold as to declare that regime change is the end-goal of American policy toward China. That may be the implication of some of the ideologically-tinged rhetoric surrounding U.S. policy, but I don't know if either administration has come right out and said so. The further you get from the executive branch, however, the more overt the calls for changing China's regime tend to become.

It's true, I think, that ideological universalism has become an end of U.S. foreign policy in its own right - not just a means to other ends. Larison contends that such universalism won't help the U.S. advance its interests with respect to China:

Other nations don’t have to want to live under a Chinese-style system to accept Chinese investment and influence, and they don’t. In practice, democrats around the world are going to be interested in pursuing their respective national interests, and insofar as China supports or does not interfere with those there is nothing about China’s domestic regime that obviously limits the influence it can have. After all, it isn’t as if China’s neighbors would be less alarmed by its moves in the South China Sea if it were a democratic state. It is fundamentally what China does, not its reigning ideology or its internal repression, that makes its neighbors wary of its intentions.

I agree, although according to the Friedburg article we both cited, the manner in which China has pursued (and to some extent defined) its interests in the South China Sea is an expression of its ideology. I'm not sure about this - partly because I'm not intimately familiar with pre-Communist Chinese history and strategic policy, and partly because this same argument was trotted out about the Soviet Union and Russia and hasn't held up all that well. (Even a "democratic" Russia under Yeltsin complained vociferously about NATO expansion in the 1990s and attempted to exert influence over her neighbors - it was just too economically weak and internally disordered to be effective.)

Bottom line: I think that between China's actions and Washington's ideological commitments, there is ample cause to believe that a Cold War-style standoff is imminent, if not already underway.

According to a new Gallup poll:

Americans broadly support President Barack Obama's plan to begin withdrawing U.S. forces in Afghanistan this year, with additional troops scheduled to leave by the end of next summer and the remainder by 2014. Nearly three-quarters, 72%, are in favor, while 23% are opposed.The vast majority of Democrats and independents, as well as half of Republicans, favor the outlines of Obama's plan, according to the June 25-26 Gallup poll.

The same poll finds a more mixed reaction to the near-term goal of having 30,000 U.S. troops out of Afghanistan in 15 months. Forty-three percent of Americans consider this number about right, 29% call it too low, and 19% too high.ort President Barack Obama's plan to begin withdrawing U.S. forces in Afghanistan this year, with additional troops scheduled to leave by the end of next summer and the remainder by 2014. Nearly three-quarters, 72%, are in favor, while 23% are opposed.

According to a new poll:

Many Persian Gulf Arabs are frightened and pessimistic about the uprisings and revolutions that are sweeping the Middle East and are too afraid to speak out against their rulers.According to a new opinion poll commissioned by the Qatar-based public forum The Doha Debates, that's the current mood among many gulf Arabs.

The online study, conducted by YouGov in June in which over 1,000 respondents were polled in 17 different Arab states, said an increasing number of gulf Arabs view the so-called Arab Spring with pessimism and fear.

And more than more half of those polled in countries in the Arabian Peninsula said they would be be "too scared" to go out in the streets and protest against their leaders.

The drone strikes being conducted in those three countries are not being done to challenge those states, but to supplement the power of those states, to act when they cannot or will not. More importantly, these are precise strikes against certain individuals, making them more like police work than like classic military action. Police work involves small arms used precisely. Drones aren't pistols, but firing one Hellfire at a Land Rover is more like a police action than it is like a large-scale military offensive with artillery barrages, armored columns, and infantry assaults. (Yes, I am shifting my position a bit from what I wrote recently about Libya.)We all understand that drone aircraft have changed warfare, but I suspect they also are changing diplomacy and foreign relations. Drones, like cruise missiles before them, have made it much easier to use force internationally. But doing this does not mean we are at war. - Thomas Ricks

Really? If Iran suddenly developed the wherewithal to fly a drone over suburban Virginia and blew up the house (and wife and kids) of a man it claimed was in the CIA conducting a terror campaign against Iranian nuclear scientists, I think the U.S. would consider that bombing an act of war, or at the very least an act of terrorism. It certainly wouldn't consider it "police work."

According to a new poll from Ipsos MORI:

New research... shows that three in five global citizens (62%) oppose the use of nuclear energy – a quarter (26%) of those have been influenced by the recent nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan.The latest Ipsos Global @dvisor survey shows that support for nuclear energy is far below that for solar power (97%), wind power (93%), hydroelectric power (91%) and natural gas (80%) as a source of electricity.

Just one in four (38%) adults across 24 countries support the use of nuclear energy. Support is highest in India (61%), Poland (57%) and the United States (52%).

(AP Photo)

Aaron Friedberg has a good piece in the latest issue of the National Interest on why conflict between the U.S. and China is inevitable:

Deep-seated patterns of power politics are thus driving the United States and China toward mistrust and competition, if not necessarily toward open conflict. But this is not all there is to the story. In contrast to what some realists claim, ideology matters at least as much as power in determining the course of relations among nations. The fact that America is a liberal democracy while China remains under authoritarian rule is a significant additional impetus for rivalry, an obstacle to stable, cooperative relations, and a source of mutual hostility and mistrust in its own right.

To which Larison responds:

If there is an “additional impetus for rivalry” between America and China on account of ideology, whence does this impetus come? Does it not come mainly from the American push for political change inside other countries? In other words, as Andrew Nathan says in his response:As long as the West wants to change the Chinese political system, Beijing’s rulers will, as Friedberg says, quite rationally “believe that they are engaged in an ideological struggle, albeit one in which, until very recently, they have been almost entirely on the defensive.”The question that comes to mind is this: why does the U.S. insist on waging such an ideological struggle, when it is likely to intensify any rivalry with China? There’s no question that ideology matters as much as power, but what remains puzzling is why states permit themselves to be held hostage to the dictates of ideology when these promise to fuel dangerous rivalries with other major powers.

There are, I think, two inter-related explanations for this. The first is that ideology is a form of power and states wield it when they think it helps them advance more mundane geo-strategic interests. To take the U.S.-China example - America's liberal democratic ideology is still fairly attractive globally, whereas not many people want to live in a single party communist autocracy that jails artists and Nobel Prize winners. Throwing this in China's face puts them on the defensive in the eyes of global public opinion and, by extension, makes it harder for China to plead its case on other issues of strategic importance. This is why many people who want to take a "harder line" with China over its growing "assertiveness" in Asia usually begin by urging American politicians to call out Beijing's human rights abuses.

The second explanation is that ideological parries are easy and demagogic. It's difficult, time consuming and complicated to suss out which states have legitimate claims to various pieces of aquatic territory and then to rally people around those issues. It's quite easy, by contrast, to call China (or any other state) "evil" and leave it at that.

Robert Kagan argues that continuing to nation build inside Afghanistan is actually a bargain:

Failure in Afghanistan will cost much, much more than the billions spent on this surge. What was the cost to the U.S. economy of the attacks on 9/11? What will be the cost if the terrorist groups now operating in Afghanistan—the Haqqani network, Lashkar-e Taiba, as well as al Qaeda—are able to reconstitute safe havens and the next president has to send troops back in to clear them out again? It is a peculiar kind of wisdom that can only see the problems and costs of today and cannot imagine the problems and costs of tomorrow.

This is a particularly interesting line of argument and one that I think undermines Kagan's case for the surge. First - the benchmark is not the costs of 9/11, since there is nothing we're doing inside Afghanistan that will prevent another mass-casualty terrorist attack inside the United States. There are multiple countries that play host to al-Qaeda cells and there is even the possibility of a small number of U.S. citizens banding together to commit some atrocity. Even a large-scale withdrawal from Afghanistan would not be so comprehensive as to leave the U.S. with no means of collecting intelligence or targeting terrorist camps. It is difficult - though not impossible - to imagine a scenario whereby al-Qaeda is able to get itself reconfigured in Afghanistan to the point where they can launch a sophisticated mass-casualty terrorist attack against the continental United States. They have been trying to do so from within Pakistan to no avail and it is far easier to travel from Pakistan to the UK and then from the UK to the U.S. than to travel from Afghanistan into the West.

Still, it's happened once so let's assume for the sake of argument that it does indeed happen again. What would it cost the U.S.? There's no fixed number for the "costs of 9/11" as such, but there are estimates of the economic toll the attacks wrought. The estimated economic cost of 9/11 was in the neighborhood of $40 billion in insured losses and $28 billion in property damage. Other estimates range from $50 - $100 billion in economic costs of the attacks themselves. A World Bank study estimated a $90 billion drop in national income. Finally, a study (pdf) by the Congressional Research Service concluded "that 9/11 is more appropriately viewed as a human tragedy than as an economic calamity. Notwithstanding their dire costs in human life, the direct effects of the attacks were too small and too geographically concentrated to make a significant dent in the nation’s economic output."

This doesn't capture all of the economic costs of 9/11, since it led to the creation of new bureaucracies and the war in Afghanistan. And it obviously ignores the devastating human toll, which must be a vital part of any cost/benefit analysis. Still, I think those are serviceable numbers. So at the high-end, the 9/11 attacks cost the U.S. $100 billion. For the fiscal year 2010, the U.S. spent $105 billion in Afghanistan. This year, the figure is expected to be $108 billion. This spending also doesn't capture the human costs nor the costs of long-term care for the wounded who return home unable to work and in need of care. Nevertheless, it seems that it's costing the U.S. far more to conduct a counter-insurgency inside Afghanistan than the economic damage wrought by 9/11.

But Kagan does helpfully elucidate the central argument: the war in Afghanistan is about keeping the U.S. homeland safe from terrorist attacks. Keeping the Taliban from ruling parts of Afghanistan is a means to that end - not the end itself. Properly framed, there are obviously "less expensive" ways of keeping al-Qaeda from attacking the United States.

It's also worth stating that the prospect that anyone will die from terrorism is vanishingly small:

Just to give you some context here, one of my friends, an astronomer, has calculated the worldwide chance of anyone being killed by international terrorism outside of war zones over an 80-year lifetime, assuming, incidentally, that every several years there is another 9/11. It comes out to be 1 in 80,000. Since he is an astronomer, he has also calculated the chance of being killed by a comet or asteroid over a lifetime of 80 years, and it comes out to be about the same.

In a post below, Benjamin Domenech argues that Jon Huntsman's foreign policy views are not those of a Republican:

Whether you agree with them or not, even supporters must concede that Huntsman's foreign policy views are a clear rejection not just of George W. Bush, but of thirty years of the views of Republican nominees on the proper attitude toward war fighting and engagement. One does not have to accept the view of Washington's neoconservative elite in order to take a view of America's role in the world that has been consistent in the Republican Party since the post-Nixon era. And Huntsman's foreign policy team - which includes former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, CFR head Richard Haass and former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, the leaker of Valerie Plame's identity - has already sparked concern among Jewish groups that Huntsman's views on America's relationship with Israel could be as out of sync with Republican values as the rest of his portfolio.

I wonder about this. First, as Ben notes, Huntsman's foreign policy advisors are all... Republicans. Not only that, they're Republicans who have all held senior foreign policy making positions in Republican governments following the Nixon administration. Don't their views and input qualify as authentically Republican?

Second, the Huntsman position that is most at odds with what Ben defines as Republican foreign policy is the argument that the U.S. must withdraw troops from Afghanistan at a faster pace than what General Petraeus reportedly recommended to President Obama. Disagreeing with the military is not only not a rejection of 30 years of Republican foreign policy making - it's completely consistent with George Bush's foreign policy. Defense Secretary Rumsfeld was famous for questioning and even over-riding the military advice of his commanders. Rumsfeld remains, I presume, a Republican.

What Huntsman's initial campaign rhetoric does suggest is that he's willing to question some cherished foreign policy orthodoxies of the neoconservative wing of the Republican party. I think there's room to do that and still qualify as a Republican.

According to a new Rasmussen poll:

Nearly one-half (48%) of Likely U.S. Voters think the al Qaeda terrorist organization is weaker today than it was before the September 11, 2001 attacks on America.A new Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey finds that only 11% of voters think the terrorist group is stronger today, despite the killing last month of its leader Osama bin Laden. Thirty-two percent (32%) say al Qaeda’s strength is about the same now as it was prior to 9/11.

By comparison, in a survey last September, 36% thought al Qaeda was stronger than it was before the 9/11 attacks. Only 25% disagreed and felt the terrorist organization was weaker.

Just over a month ago, an irresistible slice-of-life story jumped the divide between Afghan and western media.

National Public Radio was the first to report on the trend story of Afghan aversion to the number 39:

It’s hard to find a credible story to explain what exactly it means, but everyone knows it’s bad. Many Afghans say that the number 39 translates into morda-gow, which literally means “dead cow” but is also a well-known slang term for a procurer of prostitutes — a pimp.In Afghanistan, being called a pimp is offensive, and calling someone a pimp could carry deadly consequences. Similarly, being associated with the number 39 — whether it’s on a vehicle license plate, an apartment number or a post office box — is considered a great shame. And some people will go to great lengths to avoid it.

Three weeks later the Wall Street Journal weighed in on the conspiracy theories swirling around the growing taboo:

One rather credible conspiracy theory contends that the entire 39 mania has been inflamed by underhanded Kabul car dealers.Kabul car dealer Mahfuzullah Khairkhwa, who has 39 on his own license plate, admitted that, at the very least, he takes advantage of the curse to turn an easy profit.

“The problem is only in Kabul,” said Mr. Khairkhwa, who conceded that he could knock several thousand dollars off the purchase price of a car in Kabul with 39 on its plate and then turn around to sell it for a profit in the surrounding provinces, where the urban legend has yet to spread.

The head of the union of car dealers in Kabul offered a retort in a Reuters piece this month:

Najibullah Amiri, blames corrupt police officers for fanning the trend.The issue has gained prominence just as number plates for Afghan cars — which carry five digits — rolled over from the series that starts with 38, to a new series that starts with 39.

Amiri said officials at the police traffic department charge buyers between $200 and $500 to change a “39″ number plate for a new car to something less offensive.

This is not the first salacious episode involving Kabul’s automotive fleet. As the “39″ story was breaking, drivers were urgently removing rainbow decals that had begun arriving stuck onto imported cars and became fashionable until conservative Afghans learned they were also gay pride symbols.

Rainbow stickers can be peeled off but Kabul’s problem with pimp-mobiles has, overnight, thrown the city’s booming car sales industry into chaos. Dealers are reporting that “thousands of dollars of stock is now sitting unwanted in their yards, with even a prime condition vehicle almost unsaleable if its plates bear the now-hated numerals.”

To read the rest of this article, visit Forbes.com, where it was originally published.

The most tedious and erroneous meme to grip the 2012 campaign season is now being peddled by no less a figure than historian Niall Ferguson. Ferguson's hook is that the U.S. is indulging in a spat of "IOU-Isolationism." Writes Ferguson:

Welcome to the brave new world of IOU-solationism—the theory that strategic calculation takes second place to nasty fiscal arithmetic. After all, as former secretary of state James Baker has pointed out, interest payments on the federal debt could exceed defense spending in less than a decade. The Congressional Budget Office has even figured out how much cash could be saved by reducing the number of war-ready troops to just 45,000 by 2015: more than $400 billion over the next five years.

The trouble with holding up complaints about cost from Republican candidates like Romney or Bachmann is that it tells us nothing about a worldview. When it comes to "IOU Isolationism" there's no ideological or strategic objection to Washington's interventionism, just an accounting one. In other words, it has all the hallmarks of a shallow, partisan critique. Economic cycles ebb and flow. Eventually (one hopes) the U.S. will enjoy a bout of more vigorous growth. What will the IOU Isolationists that Ferguson fears do then? I suspect most of them would slide right back into the interventionist consensus.

Ferguson's counter-argument to this phantom menace of isolationism is that we can too afford it. To which one must answer: so what? I can "afford" to light a dollar bill on fire every day for the month of July. It wouldn't bankrupt me or deprive my children of food. But why would I do it?

(AP Photo)

I was travelling during President Obama's Afghan speech and after reading and abosrbing the commentary surrounding it, I think it's clear that President Obama was faced with an impossible rhetorical task - he had to explain to the United States that it won, then lost, the Afghan war.

The problem that has plagued the Afghan war from the start has been Washington's inability to define a narrow, achievable objective. Since January 2002, the U.S. squandered a quick and limited victory against the Taliban and al-Qaeda by larding on additional objectives involving the political structure of the Afghan state. The basic idea was noble enough - the U.S. would help rebuild an Afghanistan that could forge a terror-free, post-Taliban era.

Unfortunately, the move from a limited goal of destroying al-Qaeda's safe haven and killing those responsible for 9/11 to the more ambitious goal of creating a post-Taliban Afghanistan was well beyond anything the U.S. had the capabilities, resources or will to achieve. It was a goal at odds with how bin Laden's global terror network had evolved since losing its Afghan safe haven. It was also premised on the debatable proposition that regular Afghans would staff a national army tasked with fighting and dying to advance American policy priorities.

The Obama administration has paid lip service to this reality, publicly ratcheting down U.S. goals, but rather than adjust tactics it simply doubled down on the original proposition that Afghanistan could be rebuilt (i.e. "stabilized") to the point that the U.S. could leave the place relatively in tact before departing.

After listening to the president's speech, I believe Obama wants to appear committed to unwinding the U.S. nation building effort, but he is still bound by an orthodoxy that insists that the U.S. can build an Afghan state that's to its liking. It's an understandable, even commendable, impulse. It is also a counter-productive one.

(AP Photo)

A cruder, more simplistic president from a bygone era might have couched the war in terms of our effort to win. For Obama, the paramount goal is ending, not winning. But ending “responsibly” — which in the case of Afghanistan may mean ending with enough of an interval of relative stability that our exit doesn’t seem an obvious defeat.Obama’s antiwar supporters trotted out the old chestnut from the late Sen. George Aiken during Vietnam and advised that in Afghanistan he should “declare victory and get out.” As it happens, their counsel was much too hawkish: Obama would never allow himself to declare victory, even insincerely and opportunistically. - Rich Lowry

That reads to me like a back-handed swipe at the Bush administration's handling of the Iraq surge, no? I suppose one could make the case that the Obama administration and its supporters should be handling Afghanistan's wind-down in the same fashion, declaring "victory" where none is evident. It's just odd to hear this from a leading conservative pundit.

For my part in our brief interview with House Armed Services Chairman Buck McKeon (R-CA) today, I asked whether the era of the Republican hawk is over, or just on hiatus till after the next election. He had an interesting response.

"Conservative Republicans have a three legged stool: defense, fiscal responsibility and social issues. Right now the stool is a little out of balance because fiscal matters are dominating everything, because of the economic shape we're in," McKeon said. "And when the Chairman of Joint Chiefs comes and tells us our most important defense need is our economic stability, that gets a lot of people thinking that's all we should be talking about, to the point where some of them are saying 'Defense should be on the table, Defense should be cut.'"

This fits, of course, into larger concerns Republicans have about the increasing divide between the Washington foreign policy elite and the base of the party - not just the Tea Party, but other fiscal and social conservatives as well. While several Tea Party favorites maintain a generally hawkish stance on Afghanistan and other fronts, their attitude toward Libya has been frustration and disagreement from day one. A recent letter signed by a roster of former George W. Bush appointees and neoconservatives on the issue contains little in the way of anyone who seems to have a firm connection with the right's base. (A chat with an average member of the Tea Party does not typically reveal a high approval rating for William Kristol and Karl Rove, in case anyone was curious.)

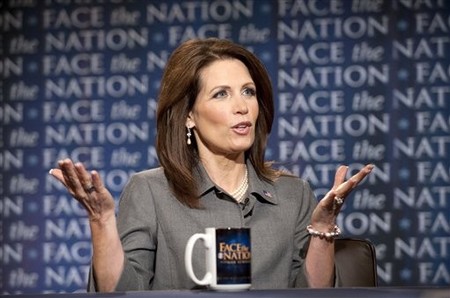

When it came time to vote today, McKeon was with the majority of Republicans, but on the opposite side from 89 of his members who successfully blocked an attempt to approve limited funding for NATO/U.S. efforts in Libya. Included in opposition are several darlings of the Tea Party, such as Michele Bachmann, Allen West and several other freshmen.

The question is whether this divide between the neoconservative foreign policy elites and the more conventionally conservative voting base on the right will grow to affect other areas of national security policy as well, beyond just things branded as "Obama's war." Without respected and serious go-betweens who don't have prior bad blood with the base, it's hard to see how McKeon's stool will be rebalanced.

(AP Photo)

Foreign Policy's Josh Rogin reports on an interview this morning with House Armed Services Chairman Buck McKeon (R-CA), where the chairman claimed the White House mismanaged their outreach on the Libya issue from day one - with sheer exhaustion as the justification. An excerpt:

On March 17 -- the same day that Obama was pursuing the authorization for war at the United Nations and two days after he decided he wanted to attack Libya -- the president had a 90-minute lunch with House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) but never mentioned Libya once, McKeon said. McKeon left Washington that night, only to receive a phone call 10 a.m. Friday morning, saying, "The president wants you in the White House in an hour for a meeting.""It's like at the last minute somebody thought ‘here's something we should check off, talk to the Congress,'" McKeon said.

When Clinton and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates eventually did come to Capitol Hill to brief Congress a week later, someone asked Clinton directly to address the issue of Congressional authorization and the War Powers Resolution.

"[Clinton] said, paraphrase, ‘It doesn't matter what you think, we're doing what we're doing.'" McKeon said. "I heard from a lot of people on both sides of the aisle that that really bothered them."

"Somebody else told me Secretary Clinton was living on about 3 or 4 hours sleep a night. So I just gave her the benefit of the doubt on that, I figured she was just tired and stressed when she made that comment," McKeon added.

McKeon then asked Gates to brief his committee for 3 hours, but Gates negotiated down the amount of time, telling McKeon, "I am exhausted... just physically," McKeon said.

Communication with Congress did not improve from then on, leaving lawmakers to come up with their own views on the war, McKeon said.

"There are a lot of people in the conference that feel the president has violated the constitution. And yet, some of those same people, they're not opposed to the mission in Libya," McKeon said." They think if he had met with Congress or in some way done a better job of setting up what he was going to do, they would feel much more comfortable and we wouldn't even be at the point where we are at."

Gentlemen,Whilst marching from Portugal to a position which commands the approach to Madrid and the French forces, my officers have been diligently complying with your requests which have been sent by His Majesty’s ship from London to Lisbon and thence by dispatch to our headquarters.

We have enumerated our saddles, bridles, tents and tent poles, and all manner of sundry items for which His Majesty’s Government holds me accountable. I have dispatched reports on the character, wit and spleen of every officer. Each item and every farthing has been accounted for with two regrettable exceptions for which I beg your indulgence.

Unfortunately the sum of one shilling and ninepence remains unaccounted for in one infantry battalion’s petty cash and there has been a hideous confusion as to the number of jars of raspberry jam issued to one cavalry regiment during a sandstorm in western Spain. This reprehensible carelessness may be related to the pressure of circumstance, since we are at war with France, a fact which may come as a bit of a surprise to you gentlemen in Whitehall.

This brings me to my present purpose, which is to request elucidation of my instruction from His Majesty’s Government so that I may better understand why I am dragging an army over these barren plains. I construe that perforce it must be one of two alternative duties, as given below. I shall pursue either with the best of my ability, but I cannot do both:

1. To train an army of uniformed British clerks in Spain for the benefit of the

accountants and copy-boys in London or, perchance…

2. To see to it the forces of Napoleon are driven out of SpainYour most obedient servant,

Wellington

The above letter - dated August 11th, 1812, and addressed to the British Foreign office in London - is attributed to the Duke of Wellington who, at the time, was waging his Peninsular Campaign. The war for the Iberian Peninsula, which would thrust the general to prominence, marked an early example of modern warfare. For it was on the Spanish plains that pitched battles between standing armies of professional soldiers gave way to the spontaneous emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare (the term guerrilla, being the diminutive of guerra, Spanish for “war” or quite literally “little war”). The British press quickly seized on the novel uprising: for the first time, peoples, not princes, were in rebellion against the “Great Disturber.”

To read the rest of this article, visit Forbes.com, where it was originally published.

In a 2012 Republican presidential field with relatively little foreign policy heft, Jon Huntsman has it in spades. The former ambassador and oft-traveled billionaire, heir to a massive chemical conglomerate fortune, is one of the most globally minded candidates in a field of otherwise parochial, or even isolationist, figures within the party.

Talking to his associates from his time in China, one hears near-universal respect for the man and his views of America's role within the world - even to the point of turning his time away from the states in China into a potential political asset, an instance of confronting communists with a case for freedom. They'll tell you Huntsman truly does view his role as one of duty and service to the nation - even to the point of setting aside his Mormon religious views on drinking alcohol to drink the disgusting baijiu liquor which is mandatory at Chinese events (I'm told Huntsman would drink the clear alcohol once and then switch to water, hoping no one noticed after the first round). Huntsman's tenure as ambassador was marked by only one significant public gaffe, a bizarre incident where he attended, then fled, from a Jasmine Revolution protest, attracting attention for the large American flag patch on his arm (he claims he stumbled across the protest by accident).

Yet for someone whose campaign has already adopted a view prioritizing global issues, and whose announcement in front of the statue of liberty this week was purposefully constructed to spark recollections of Ronald Reagan's run against Jimmy Carter, Huntsman's publicly-expressed foreign policy views seem to have more in common with Carter than with Reagan.

Without question, Huntsman is the furthest left of any purportedly serious candidate for the nomination when it comes to forming a response to Afghanistan. His press release on the president's remarks this week emphasized his approval for "a safe but rapid withdrawal," but his critique on NBC's Today show went much further. Asked by host Ann Curry whether he thought a drawdown of 30,000 troops by next year was too much or too rapid, Huntsman responded by saying that "I think that we can probably be more aggressive over the next year" in drawing down troops.

Despite the comparisons to John McCain's 2008 presidential run - and on the campaign and organizational side, there are many - Huntsman's statement could not be more at odds with McCain's views on Afghanistan and the necessity of preventing losses of the gains made in the past two years. Like Obama, Huntsman emphasized the need for “nation building at home” (as if the two goals are inconsistent) - but Huntsman went further, saying it was time to "get serious about what needs to be done on the ground, not a counter-insurgency but a counter-terror effort." While nearly every Republican in the race has emphasized the need to heed the advice of the commanders with on-the-ground experience on the front, Huntsman is purposefully setting himself apart in unequivocally rejecting the advice of Gen. David Petraeus and Admiral Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, from afar. More significantly, in supporting a more aggressive drawdown to be replaced by a limited counter-terror strategy, Huntsman is essentially endorsing the view by Vice President Joe Biden - a view which proved too rapid and risky even for President Obama.

Whether you agree with them or not, even supporters must concede that Huntsman's foreign policy views are a clear rejection not just of George W. Bush, but of thirty years of the views of Republican nominees on the proper attitude toward war fighting and engagement. One does not have to accept the view of Washington's neoconservative elite in order to take a view of America's role in the world that has been consistent in the Republican Party since the post-Nixon era. And Huntsman's foreign policy team - which includes former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, CFR head Richard Haass and former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, the leaker of Valerie Plame's identity - has already sparked concern among Jewish groups that Huntsman's views on America's relationship with Israel could be as out of sync with Republican values as the rest of his portfolio.

Rather than playing games of triangulation, Huntsman may simply be saying what he believes. But perhaps the reason he's caught fire with so many leading media figures is that he's saying things they tend to agree with. This is all well and good, and coherent so far as it goes. It's just not very Republican.

(AP Photo)

There was little surprising about President Obama's announcement last night that he will withdraw 10,000 U.S. troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2011, increasing to the full level of his 33,000-troop surge by the end of next summer. But there are a number of questions sparked by his remarks; questions we won't know the answers to for some time, raising concerns about the long-term results of this decision.

Despite the intonations of some commentators about its catastrophic consequences - Jen Rubin at the Washington Post called it "the most irresponsible speech ever given in wartime by a U.S. president," while Dana Milbank is calling it Obama's "Mission Accomplished" moment - this actually can be measured as a slight win for those forces within the administration who argued for a slower drawdown than was politically preferable. It certainly was not a victory Senate Armed Service Chairman Sen. Carl Levin, who wanted 50 percent more, or for Vice President Joe Biden, who reportedly wanted forces withdrawn by the beginning of next summer.

The real test of how much of a victory it is for the commanders likely depends on how much leeway the White House gives them on which 10,000 personnel come home - support battalions, or warfighters. Yet while most commentators are focused on the number, it is the timing of this withdrawal's second phase that should concern people more than the number. As the New York Times notes this morning, "the most significant effect of President Obama’s latest orders will be felt at this time next year, when as many as 23,000 American troops who would have been on missions at the peak of the summer fighting season will instead be packing for home."

And while I typically reject William Kristol's views on foreign policy, he seems right on this score: This is a timing decision made with the 2012 election primarily in mind, not the security picture or in anticipation of changing facts on the ground.

Triangulating works as domestic politics for a reason: Your metric for judging the outcome is making a decision placed between two poles that appeals to the largest portion of the electorate. This is less wise when it comes to strategic decision-making, particularly considering the potential consequences of this decision not just for Afghanistan or for American security, but for the nearly 70,000 U.S. troops who will remain in Afghanistan after this drawdown is complete.

It's hard to shake the feeling that Obama may come to regret deploying this approach to his decision-making process at some point in the future. But as Kori Schake noted prior to the remarks last night: "It's the president's choice. That's what he gets elected for."

And the consequences, for good or ill, could come to define his presidency. Let's hope he's right.

Last night U.S. President Barak Obama announced the beginning of the end of his Afghan surge. Ten thousand U.S. troops will be home by the end of the year, with the remaining 20,000 surge troops returning stateside by next summer. That will leave approximately 70,000 to focus on Afghanistan’s restive borders to the south and east. Some of those will trickle back by 2014, when full security of the country is to be handed over to Afghan forces. Others are likely to be stationed at semi-permanent bases across the country into the near future.

The drawdown is seen as deeper and faster than anticipated by the Pentagon and, rather than signaling overwhelming success, reflects the heightened fiscal pressures that have descended on Washington along with the uncertainties surrounding the broad nation-building mission in the wake of Osama bin Laden’s death.

To read the rest of this article, visit Forbes.com, where it was originally published.

As President Obama prepares to tell us how many troops he will withdraw from Afghanistan, it's worth pointing out that the U.S. was never supposed to a launch a war against Afghanistan. It was supposed to be against several hundred Arabs and a hodge-podge of other nationalities who had taken up shop in Afghanistan to plot terrorist attacks, plus a slice of the Afghan population that thought sheltering them was a good idea. When the Bush administration largely accomplished that in early 2002, it decided to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory by turning the war into a quest to give Afghanistan something it had not had in decades: a stable government.

This was a classic example of moving the goal posts, and it has been costly.

Maybe, if Lindsey Graham has his way:

Nevertheless, Sen. Graham, who two years ago spent a pleasant time visiting Tripoli and discussing with Qaddafi the possibility of providing military aid, now is relentlessly beating the war drums for U.S. and NATO escalation. And he views Libya as a template for military action elsewhere. Appearing on CBS’s Face the Nation, he declared: “If it made sense to protect the Libyan people against Qaddafi, and it did, . . . the question for the world is have we gotten to that point in Syria?” Graham, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, added: “We may not be there yet, but we’re getting very close.” He explained: “It has gotten to the point where Qaddafi’s behavior and Assad’s behavior are indistinguishable . . . You need to put on the table all options, including a model like we have in Libya.”

At the risk of sounding "isolationist" let's just point out that the Libyan "model" has yet to produce the desired results and the tab continues to grow. Why this option would be "on the table" is beyond me.

The Wall Street Journal highlights a potential challenge in a post-Gaddafi Libya:

The feud between Misrata and Tawergha offers a stark example of the challenges Libya will face in reconciling communities that found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict when Col. Gadhafi leaves power.Misrata, Libya's third-largest city and its commercial hub, has been viewed with suspicion by Col. Gadhafi, who sought to promote minority groups like the Tawerghans and some Bedouin tribes in the area to counterbalance the might of the tightly knit white merchant families here.

Before the siege, nearly four-fifths of residents of Misrata's Ghoushi neighborhood were Tawergha natives. Now they are gone or in hiding, fearing revenge attacks by Misratans, amid reports of bounties for their capture.

The rebel leadership in the eastern city of Benghazi says it is working on a post-Gadhafi reconciliation plan. But details are fuzzy and rebel leaders often resort to platitudes when dismissing suggestions of discord, saying simply that "Libya is one tribe."

It would be grimly ironic (but not unexpected) if a war fought ostensibly to avert one humanitarian crisis gave rise to another, potentially more severe, catastrophe in its wake.

(AP Photo)

Secretary Gates is worried:

Aboard the Pentagon jet on his last foreign trip as secretary of defense, Robert Gates takes a moment to peer across the American horizon—and the view is dire: the U.S. is in danger of losing its supremacy on the global stage, he says.“I’ve spent my entire adult life with the United States as a superpower, and one that had no compunction about spending what it took to sustain that position,” he tells NEWSWEEK, seated in a windowless conference room aboard the Boeing E-4B. “It didn’t have to look over its shoulder because our economy was so strong. This is a different time.”

A pause.

“To tell you the truth, that’s one of the many reasons it’s time for me to retire, because frankly I can’t imagine being part of a nation, part of a government … that’s being forced to dramatically scale back our engagement with the rest of the world.”

Aside from the yawning disparity in military spending, who is talking about "scaling back our engagement" with the rest of the world? There are a few politicians expressing skepticism about bombing specific parts of the world, yes, and still others questioning the wisdom of deficit-financed nation building. But that does not equate to a growing unwillingness to "engage" with the world.

Nick Trevethan says that investors aren't buying Nouriel Roubini's China pessimism:

Famed market bear Nouriel Roubini may be talking down China, but resource firms are betting billions that rapid urbanization and economic growth will soak up the country's massive infrastructure investment and prevent a hard landing.They are buying up competitors, investing in new capacity and speeding expansion projects to feed breakneck growth in raw materials demand in the world's top consumer of commodities.

While the prison crisis descends into chaos in Venezuela and the country starts buying electricity from Colombia, Hugo Chavez is still in Cuba, following last week's surgery for a mysterious "pelvic abscess" of so far undisclosed etiology.

From there he raised the country’s debt ceiling by 83 percent.

According to Noticias 24, Fidel and Raul Castro stopped by Chavez's hospital room, where he remains "recovering ... in needed rest."

As you can see, Chavez needed to prop himself up on Fidel and Raul, which is saying something. All the same, Chavez continues to rule Venezuela from afar.

Venezuelan News and Views looks at Chavez-as-Viceroy:

I do not know about you but never have I felt as much a Cuban colony as I am feeling this week, and it is only Tuesday. Not only now our orders come directly from Cuba where Chavez prefers receive treatment that he could perfectly receive at home, and probably of a much better quality, but his latest decisions reek of old style colonialism.First, that he prefers to receive treatment in Cuba. The pictures of him arriving there were of a very smiling, very upright Chavez, not someone in pain that would receive within hours "emergency" medical treatment. I, for one, could not are less about what ails Chavez, nor would I begrudge that he receives medical treatment for emergency wherever in the world he is. However, I, for one, do not buy for a second the emergency status. For me, it looks like those African presidents that fly to Europe even for dental treatment. To Paris, preferably.

Second, the 1999 constitution, written mostly by Chavez, has very specific provisions to deal with temporary absences of the president.

...Third, he appoints his baby brother as the new tsar of electricity. What merits Argenis Chavez may have are not the point. The point is that in time of crisis, outside of the country, in a sector where huge investments are required urgently if he wants to be reelected in 2102, Chavez can only trust a sibling which has already been amply tainted with accusations of corruption. Just as ancient Spanish Viceroys traveled to the Americas with family and friends to occupy the key posts in their new charges.

Everybody is speculating as to Chavez's malady, particularly since Chavez, who for years has done his interminable TV and radio shows several times per week (averaging 43 minutes per day since he took power in 1999), has limited himself to a single telephone call into state-run television for the last ten days.

Cross-posted at Fausta's blog.

Rioting and looting left cars burned, stores in shambles and windows shattered throughout the city center as police fired tear gas to control the mob. One hundred and fifty were injured and close to 100 were arrested. Three stabbings were reported, and one victim sustained serious head injuries. Nine police officers were hurt. Fifteen cars were burned, including two police cruisers. Perhaps as many as 50 businesses were ransacked, with damages easily climbing into the millions.

The local police chief described the instigators as "criminals and anarchists." "Organized hoodlums bent on creating chaos, incited the riot," said the mayor.

The rabble was not roused by the burning of holy books by foreign occupiers. It was not in reaction to brutal and repressive Middle East dictators, nor was it against the imposition of harsh austerity measures within a currency bloc. No, these riots were in response to cross border aggression against cultural heritage. On Wednesday the Vancouver Canucks lost the Stanley Cup final (that's ice hockey) to the Boston Bruins.

It was only four months ago that The Economist awarded Vancouver, for the fifth straight year, the title of the world's most livable city, with Melbourne ranking a close second. The accompanying report explained what makes a high-ranked city:

Cities that score best tend to be mid-sized cities in wealthier countries with a relatively low population density. This often fosters a broad range of recreational availability without leading to high crime levels or overburdened infrastructure. Seven of the top ten scoring cities are in Australia and Canada, where population densities of 2.88 and 3.40 people per sq km respectively compare with a global (land) average of 45.65 and a US average of 32.

Unfortunately, in this case, recreation led directly to high crime levels. But, chin up Vancouver; while Most Livable City 2012 might have just slipped away, there's always next year for the Cup. In the meantime, all the non-anarchists can hide out in Melbourne.

“I brought this picture out for you, Henry,” Donald Rumsfeld says to Henry Kissinger, proffering a framed black and white photo of a line of men sitting across from each other at a diplomatic gathering. “It was right after Vladivostok.”

“When you went to China with me?” Kissinger asks, perking up.

“I took you into China and introduced you to Zhou Enlai,” Rumsfeld says, with a smile and a slight chuckle. “No, no, that’s not how it worked.”

“No, but he was still alive, actually,” Kissinger says.

“Yes, you met with him,” Rumsfeld says. He has one hand in the pocket of his trademark fleece vest. “But here’s Deng Xiaoping, your friends Habib, and Winston Lord, and George Herbert Walker Bush, and Phil…”

“I remember that meeting,” Kissinger says, peering through his spectacles at the shadowy photo. “With Deng.”

The two veterans of a thousand policy arguments and diplomatic quarrels are quiet for a moment, looking into the past, at two lines of men divided by ideas and the sea, individuals who would shape the world for half a century and more.

Rumsfeld was hosting Kissinger - who inscribed a book to the two-time Defense Secretary as an “occasional adversary and permanent friend” - to promote the oracular diplomat’s new book, On China. It is a broad collection of his thoughts and anecdotes, with some reminiscing and a few policy prescriptions gained both from his more prominent diplomatic visits, conversations with Chinese leaders, and the over fifty times he’s been in the nation since. As the original, popular proponent of the long arc theory in respect to China, the former Secretary of State and National Security Advisor is now putting forward a recommendation for complementary growth and what he hopes to be a path to avoiding adversarial confrontation, written in longhand and released the same week as his eighty-eighth birthday.

Kissinger draws comparisons which may be familiar to those who’ve followed his work and speaking closely in recent years: he draws contrasts between U.S. and Chinese approaches to deterrence and international relations based on the intellectual games of the West and East - the direct adversarial approach of Chess and the longer, subtler games of encirclement in Go - as the models for explaining activity and decisionmaking.

“For the West, deterrence is the assembling of superior power either to prevent an attack or to crush the enemy if he does attack. Our concept of deterrence is aimed at capability. Their concept of deterrence is more preemptive - offensive deterrence, aimed at the psychology of the opponent,” Kissinger says, pointing to the Sino-Indian conflagration of 1962 as a real world example of this phenomenon.

The book arrives as concerns are rising that China’s current regime, due for a massive change in 2013, has traded material prosperity and racial superiority for legitimacy, even at the cost of more or less destroying any coherent communist ideology. While they’ve been successful in charting this path for more than two decades, it's been fueled in part by the short-term economic surge that comes from a birthrate-collapse-induced demographic imbalance. As China ages and its export-driven economy necessarily slows, the possibility for further upheaval is significant.

How significant depends on who you ask, and I queried Kissinger on this point. Accepting the Chinese view of cyclical nature of collapsing and rebuilding society: does he think another dynastic collapse is in the foreseeable future? Or is dynastic collapse more or less impossible without a massive wave of young people to fuel it?

“I know that the Chinese leaders that I know and have seen in action are all obsessed with the concept of stability,” Kissinger said. “And that is for two reasons - one is that with that many people the challenge of governance is just stupendous. And when you have a people who are as individualistic as the Chinese are, it becomes even more challenging.”

“When you go to a small town - which is what they call a place of 500,000 people - it looks as if everyone is on the street doing something, a tremendous amount of activity. And I said to myself, how can they possibly know in Beijing what is going on here?” Kissinger said. “I took a trip with my wife down the Yangtze, and stopped at every river town, and had to ask - how could you believe, in Beijing, what the reports say? This was still when they were a totally state-controlled economy. This being the case, there is always the danger of centrifugal forces, and it’s happened often enough in Chinese history.

“The way these issues are often put are ‘should the young people take over?’ And I’m not saying they should or they shouldn’t. I’m saying that whenever the system collapses in China, whatever the system, I know no example when this collapse did not usher in a period of tremendous chaos and tremendous bloodletting, so the idea that things go from where they are - to one revolution in a square - to change, that is not even happening in Egypt.”

Kissinger related a story from his experiences on a prior trip, under Mao, which illustrates the way local officials were even then navigating around the mandates from Beijing to meet the needs of their people.

“I went to a town in the south of China, and when I landed there, I saw two Boeing 737s sitting at the airport. And I asked the governor, ‘what are these planes doing here?’ And he told me, ‘I’m starting an airline.’ I said, ‘what are you talking about?’ And he said, ‘we are halfway between Hong Kong and Bangkok, and my people have to go to Hong Kong in order to go to Bangkok. So I’m starting an airline that will take them directly there.’ And I said, ‘how is that happening?’ And he told me ‘we pay our taxes, but we have a lot of resources, so I am doing it myself.’ Now, in Soviet Russia, just for having that thought, you would’ve been boiled in oil.

“So you have these forces in China which make the central leadership nervous,” Kissinger said. “I saw an economic study a few years ago, from Johns Hopkins, which showed that roughly 25 percent of what is listed as foreign investment in China is actually Chinese money which is laundered outside the country and then reinvested into the country as foreign investment because it gets special tax treatment. This is not a good situation, and it is a danger always felt by the government in China.”

The focal point for questions of conflict with the United States regarding China’s future is their resource mining, primarily in Africa but in other parts of the world as well (it seems ironic that the United States would be laboring so hard in Afghanistan, for instance, to keep the roads clear for China’s conflict mining). While China has thus far limited their impact to the drawing of these resources, most of those African states are states in name only, making counter-influence largely the result of bribes to the ruling classes. I was curious whether Kissinger would agree with the notion that China has effectively colonized large swathes of Africa as part of this push for minerals, and whether, given the growing race for raw materials, the U.S. can or should respond.

“Right now, China is going to Africa primarily for resources,” Kissinger said. “And they have stayed miles away from political control. But of course when you own the largest resource in any country, it gives you considerable influence. In order to keep public support, they are doing a lot of infrastructure projects. Insofar as gratitude produces political support - it does not always - their influence in Africa is undoubtedly growing.”

Yet is a balancing act even possible here? The United States is unlikely to start a war to stake out minerals claims, and doesn’t typically involve itself in public-private operations as the Chinese do - most private companies, as a rule, don’t have the U.S. Treasury behind them to engage in a massive international resource war.

“The negative for them in this approach is that they don’t have experience dealing with developing countries, and they’re very self-confident - so they often appear heavy-handed, and are heavy-handed. And of course, you cannot omit the possibility that this will merge into a more explicit political control,” Kissinger said. “I would analyze their present view to be that they do not want direct confrontation with the United States because they want their economy to continue to grow. So for the short term, I expect them to continue their present pattern. But as the process continues? It is something to think about.”

One aspect of this which makes things more complex is that China is not harvesting those resources for sale on the international market but rather for their own use. Many of those materials are rare earths we are unable or unwilling to harvest domestically, that can be and are used for high-tech industrial, commercial, and military components. The urge to respond could, therefore, be considered a relic of leftover ideas of the tie between a nation and industry in which China believes but the United States no longer does.

“Of course, if my ideas prevail, and if they are willing to play the same game - I am not saying in this book that we ought to surrender, I am saying that they have to do their fair share - we can develop what I call in the book a co-evolution. This is evolution at the same time, but not necessarily rivalry,” Kissinger said. “In that case, it can be managed. But if we cannot do that, on either side, it will turn into rivalry. But if you visualize that rivalry all over the world, it is an image of the world in continuous turmoil.”

What does seem clear is that China prizes regional hegemony and international respect, stemming in part from the memory of Ming glory and the scars of Opium War subjugation as much as the ordinary desire of any people to be considered powerful. It also wants to stake claims on several disputed territories, continental and island. Is China likely to trade old territorial claims in return for international respect, to paradoxically satisfy its present need for recognition? And if so, should the U.S. respond?

“China has led the world in GDP for 18 out of the past 20 centuries. They have never in their history had to deal with a country of equal magnitude,” Kissinger points out. “The countries that encircle them, if united, could theoretically overrun them. So foreign policy was normally, for the Chinese, management of what they call ‘barbarians’, a balancing act of pitting foe against foe… I don’t believe that the Chinese have the views the Soviets had. They generally did not expand by conquest, but by osmosis. In fact, they expanded by being defeated by people of a different culture, and then converting them to a Chinese culture. I think you will see policies that continue to follow this line.

“When we first came to China, we didn’t think we could make Mao an American liberal. We had to be concerned with the conduct of our foreign policy,” Kissinger says. “And it’s a debate that keeps going on in this country - is it our responsibility to overthrow governments we don’t agree with? Or is it our first responsibility to enhance our security by dealing with countries as they exist? If they can be modified over a period of time it is of course worth us attempting it.

“If you look at Chinese history, they’ve remained independent for thousands of years. So when a foreigner comes along and says you’ve got to change your government…,” Kissinger shrugs. “Individual Chinese dynasties have lasted longer than the whole history of the United States. So I’m more humble about what we can do in China.”

Yet Kissinger maintains that if the idea takes root that the United States is entering a period of permanent decline, it could be a very dangerous one for both parties.

“We have to learn to live with our natural potential,” Kissinger said. “We absolutely have to remain competitive, but can we move from a zero sum game? That should be the objective, but it cannot be achieved alone.”

Rasmussen polls likely voter sentiment on NATO:

A new Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey finds that 49% of Likely U.S. Voters believe America still should belong to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, formed in 1949 to counter the Communist Soviet Union. Twenty-seven percent (27%) do not see a need for the United States to still belong to the alliance now that the Soviet Union is gone. Twenty-four percent (24%) are undecided.Just 46% hold even a somewhat favorable view of NATO while 37% view the organization unfavorably. Overall attitudes are quite soft as just 7% hold a Very Favorable opinion of the group while 12% express a Very Unfavorable view. Nearly two-thirds (64%) fall somewhere in between.

Sixty-two percent (62%) of Democrats have a favorable view of NATO, while most Republicans (52%) view the alliance unfavorably. Voters not affiliated with either party are almost evenly divided in their assessments.

Afghanistan’s second vice President, Karim Khalili, the Minister of Interior, Bismillah Khan Mohammadi, MoI leadership, NTM-A Deputy Commanding General and EUPOL and German Police Project Team officials gathered for the ribbon cutting ceremony of Afghanistan’s largest premier police training facility.

So began a press release from the NATO Training Mission - Afghanistan (NTM-A). The article describes the modern training facilities that will house 3,000 cadets once construction is completed. The U.S.-funded, $106 million dollar facility has an impressive "23 barracks, eight classrooms, 23 guard towers, three dining facilities, three headquarters and administration buildings, gym, auditorium, medical facility, fire station and international trainers compound."

That fire station must have come in handy during yesterday's ribbon cutting ceremony, for, you see, the NATO public affairs officers missed a more gripping intro to their report.

Buried deep in the story was this apparent throwaway graf:

As the ceremony was concluding, a rocket impacted in the training center. There were no injuries or fatalities during the attack and dignitaries were able to safely depart the site. Wardak province has a history of sporadic rocket attacks that are the ongoing focus of Afghan and NATO forces in that area.

The Associated Press framed the incident differently:

The round crashed down and exploded within the grounds of the facility during its inauguration Wednesday, sending panicked police recruits crawling across the floor of a meeting hall and prompting bodyguards to bundle one of Afghanistan's vice presidents and the government minister in charge of police forces into helicopters and flee.

Spin is one thing but when self-congratulatory ribbon cuttings are deemed more news worthy than rocket attacks on senior Afghan politicians and NATO officials, a firm grounding in reality has somehow slipped away, if not in Afghanistan as a whole then at least in NATO's public affairs department.

Glenn Greenwald claims to be shocked that the Obama administration would priviledge American companies over those from other countries:

Earlier this month, Hillary Clinton hosted a meeting of top executives from a wide array of corporations -- Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Halliburton, GE, Chevron, Lockheed Martin, Citigroup, Occidental Petroleum, etc. etc. -- to plot how to exploit "economic opportunities in the new Iraq." And one WikiLeaks "diplomatic" cable after the next reveals constant government efforts to promote the interests of Western corporations in the developing world. Nonetheless, the very notion that the U.S. wages wars not for humanitarian or freedom-spreading purposes, but rather to exploit the resources of other nations for its own large corporations, is deeply "irresponsible" and unSerious. As usual, the ideas stigmatized with the most potent taboos are the ones that are the most obviously true.

Really? I think it's just the opposite. There's no real stigma around the idea that the U.S. seeks to maximize its economic advantage or energy security through foreign policy. What else is it supposed to be doing?

It's true, as Greenwald notes, that there is often a taboo around discussing this so blatantly and crassly at the political level. Presidents are expected to engage in ritualistic paeans to universal human rights and paint the U.S. in the best light possible. But outside of some soaring presidential rhetoric, is the idea that the U.S. would seek to advantage its commercial interests when dealing overseas a "taboo?"

Hardly.

Remember Secretary of State James Baker's rationale for the first Gulf War? "Jobs, jobs, jobs."

It was obvious from the start that one of the primary reasons the West took such an active interest in Libya's humanitarian crisis was because of its oil. There has been no shortage of articles dealing with Libya's oil, its impact on the war or the role it has played in motivating countries like Great Britain to intervene in Libya's civil war. This is hardly hush-hush.

(Mind you, I don't think it was wise for the U.S. to intervene in Libya - no matter how much oil the country has - nor do I think the military should be used to tee-up preferential resource contracts for U.S. corporations.)

In the coming weeks, President Barak Obama will announce exactly what shape the termination of his Afghan surge will take. In light of this, and in the aftermath of bin Laden's death, pundits have been falling over themselves to voice just what all this means for the future of the U.S. involvement in Afghanistan.

Defense Secretary Gates has called for a gradual withdrawal while Democrats in Congress are eager for a more hasty departure. The White House itself has said that the July drawdown will be "real" and the final decision will be based on "conditions on the ground" lining up with the president's stated objectives of defeating al-Qaeda and stabilizing Afghanistan, according to CFR.org.

Part of the calculus behind any drawdown schedule will be the progress of peace negotiations with the Taliban. Yesterday, The Express Tribune, a Pakistani newspaper affiliated with The International Tribune, ran a story alleging that, according to an unnamed source, the United States had made direct contact with Taliban leader Mullah Omar via an intermediary, a former Taliban spokesman known as Mohammad Hanif who was arrested by U.S. forces in 2007.

Rumors on high-level secret negotiations between the U.S. and the Taliban have been swirling around Kabul for at least a year. Some of this hearsay could be credible, such as talks in Germany, the Persian Gulf and Turkey, while in others instances the U.S. has been outright hoodwinked by Taliban impostors.

According to the Express article, the U.S. had offered the Taliban control over the south of Afghanistan, while leaving the north for the other political forces under American influence. However, this was rejected by the Taliban.