Richard Cohen writes:

American conservatives look at the defeats and disappointments, and they fulminate about Obama. They call him weak and inept -- and surely in some areas he has been both. But they are wrong in thinking that another person would make much of a difference. Times have changed. America's power is diminished -- relatively, for sure, but absolutely as well.

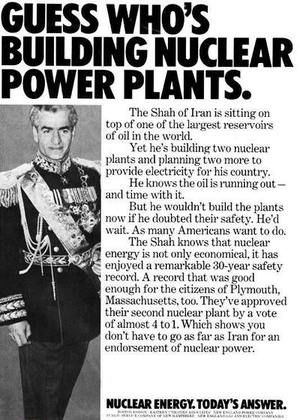

I think this is the important takeaway from this week's tripartite nuclear deal between Brazil, Turkey and Iran. While the nuclear alarmists are predictably ringing the bells of Armageddon, they do so, unbeknownst to themselves, from a position of increasing weakness. The Wall Street Journal leads the charge, insisting that President Obama do something, because, well, that's what the American president does. Absent, however, from their editorial panic attack is a feasible policy proposal for making Iran halt its enrichment, disclose all its nuclear wrongdoing and ultimately hug it out with the West.

They believe, as they so wrongly did back in 2002, that American military might alone is enough to compel global behavior and police the world's evildoers - and perhaps it was, during the Cold War. But the United States has yet to articulate a rationale for its role as global superpower in a world with multiple levers and venues for global governance, and the world's emerging powers simply aren't buying it any longer.

And this clearly flummoxes Iran hawks, who can only view American power through the lens of the presidency; they, like some of our allies in Israel, insist that the threat of a nuclear-armed Iran is the most pressing crisis facing the world, and should the American president but will it, he (or she) can give a compelling speech, pound his (or her) fist on a table or two, and the world - as it so often has in the past - will bend.

One problem: faith in American power is no longer unanimous. By pegging Iranian engagement to the nonproliferation regime, and in turn Israeli security, the Obama administration opened up a Pandora's box of nuclear populism. The plan, I'll admit, seemed a viable one at first: engage Tehran on the most commonly agreed upon and demonstrated dilemma - namely, its rogue nuclear program - and reach some kind of a deal on LEU in order to give the West breathing room for negotiation; alleviate Israeli concerns of an imminent nuclear arms race in the region; address the nuclear weapons program, and then move on to other longstanding issues in need of redress between Washington and the Islamic Republic.

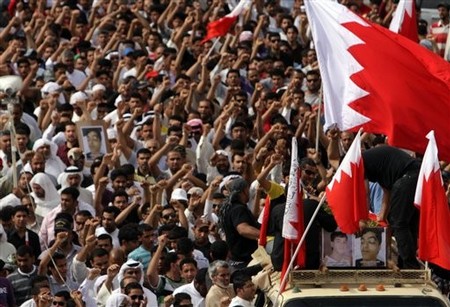

But Iran has always insisted that the nonproliferation tactic was always a pretext - a multilateral cover - for compelling Iranian behavior and, perhaps, even changing the Iranian regime entirely. And normally, this complaint would fall on (mostly) deaf ears around the globe. But Iran, to its diplomatic credit, cleverly morphed a dispute between a handful of countries into a global debate between the nuclear haves and have-nots. What started as a reasonable discussion about Iranian intransigence became a debate over the legitimacy of the NPT.

The haves versus the have-nots; the emerging world versus the entrenched - this has played out exactly as Iran had hoped.

So what now? I think the best option remaining for the Obama administration is to table the nuclear question and go down the admittedly murky and unpleasant path of grand bargain engagement. Nonproliferation and the future of global nuclear enrichment is far too important to be left in the hands of the Iranians, and the only way the revolutionary regime will play serious ball on the nuclear question is if Washington is willing to address - and redress - Iran's laundry list of grievances and gripes.

Even Israel - which would no doubt protest such a sea change - has more pressing security concerns regarding the Iranians, as the potential threat of a Tehran-fueled arms buildup in the Levant makes confrontation between Israel and Hezbollah appear more and more likely. Setting the nuclear matter aside for the time being would behoove them as well.

But this is all rather unlikely. Iran, for its own part, has a long record of diplomatic gamesmanship and deception, and Obama simply doesn't have the political cover at home to make such a gesture (and the atmosphere may only worsen come November). Obama - after months of nuclear bell-ringing - will be held solely accountable at home for failing to slay the Iranian monster, and Washington will likely creep back into its comfort zone of exceptionalism and saber-rattling toward Tehran. Iran will embed itself even deeper into its own comfort zone of anti-Westernism and global defiance, as the U.S.-Iran status quo keeps trucking along.

How this ends, I'm not sure. Perhaps multilateral sanctions will hasten a breakthrough before the midterm elections, but that's doubtful. I don't believe we're witnessing the buildup to war, but I do believe Obama's window for engagement has likely closed.

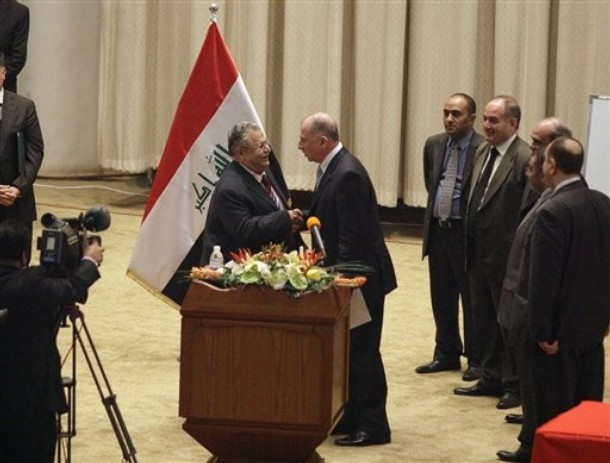

(AP Photo)